Juanita Hall, 43, has never had a song stuck in her head. She never had a favorite band while growing up. Music, movies and television weren’t a part of her life until closed captions were invented. Although Juanita has never had a melody in her head, there has always been music inside her. Juanita Hall was born deaf, but after a year of fiddle lessons, she has become a musician.

“You wanna learn that?!” Juanita looks back at her fiddle instructor in all seriousness. “Yes, I want a challenge,” says Juanita as she glances at her husband, Greg, 45, for support as he sits next to her, mandolin in hand. “That’s the most famous Kenny Baker song I know,” says instructor Liz Shaw, a 30-year veteran music teacher and all-around North Carolina spitfire. Liz critically skims the sheet music with big eyes and says, “Oh, it will be a challenge…for me too!”

“And a one, two, three…” Leather shoes tap together in unison against the musty blue rug in the basement of Blue Eagle Music. The folk-fretted harmony of “Simple Gifts” surrounds the three musicians but Juanita hears nothing. She is focused on the page and the feeling of each note.

Music lessons with Liz have become a family affair and every Wednesday the Halls load up their blue Ford station wagon with fiddle cases and music books to make the 18.7-mile commute to Blue Eagle Music. Greg and Juanita’s daughter Libby, 7, loves taking piano lessons and receiving the sparkly Disney princess stickers that show her progress in her large font piano book. Not long ago, Libby’s brother, Ben, 10, told Greg, “Hey, Dad, listen to this,” and played Beethoven’s “Fur Elise” flawlessly on the piano by ear. Ben has the most raw musical talent, but the littlest interest in taking lessons, so he plays peacefully with Lego blocks in the corner while his parents work on their fiddle finger placement.

“When [Juanita] started the fiddle, it was hard for all of us,” Greg says with a smirk. The fiddle is said to be the most unforgiving instrument to learn, ready to shriek at any beginner’s error. Juanita bought teaching videos for the violin but struggled to lip-read the instructor’s lessons because they weren’t closed captioned. It wasn’t until Juanita and Greg enlisted the help of Liz, a fifth generation folk musician, that they started to hear (and feel) progress. Liz has instructed over 1,000 fiddle, banjo, guitar, dulcimer and piano students, some of whom have had missing fingers, severe visual impairment, Down syndrome and autism. But none were deaf. Although she didn’t know how it would work, Liz told Greg and Juanita, “If you’re game, I’m game.”

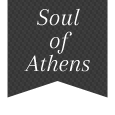

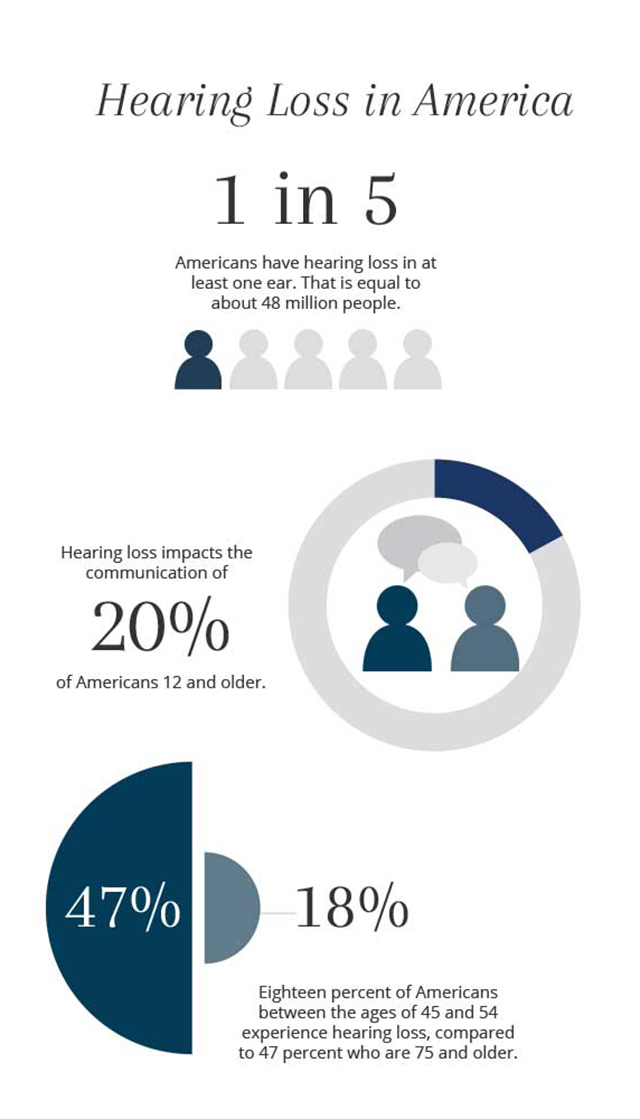

Hearing Loss

There are many types of hearing loss, and they can result in varying degrees of deafness. Here are some examples of what a violin may sound like with mild, moderate, and severe hearing loss.

No hearing loss:

Mild hearing loss:

Moderate hearing loss:

Severe hearing loss:

“Liz would help me through it, you know, and finally just one day, it felt smoother. It finally came together and I felt good. I think I can finally do this,” Juanita says. To bridge their communication gap, Liz exaggerates her bow movement and uses hand signals during lessons, such as thumbs-up, time-out, just like a baseball coach on the sideline. The biggest concern Liz had was teaching Juanita tone. “You can’t fake the tone,” she says. Bad tone, according to Liz, “will make the dog leave home when you’re learning the fiddle,” but Juanita mastered the skill in six weeks— less time than most fiddle students.

For Juanita, reading music is “like memorizing a poem.” The notes that most people hear, she feels as vibrations and the more Juanita plays, the more she is able to feel the difference between individual notes. Lower tones feel “fatter,” while the higher notes are tighter with lightness that is “just like playing air.” Juanita’s tactile experience of music can also translate visually. “I prefer the slower songs because it's prettier and I can see more pretty shapes and colors and movement,” she says.

It wasn’t until she was three that Juanita’s parents realized she was deaf. Linda Holcomb, Juanita’s mother, says her first-born girl giggled and played like any normal baby. She would even hum little tunes to herself. Linda followed the advice of parenting books, making sure baby Juanita was facing her when she spoke. Little did she know, she was teaching her daughter how to lip read. It wasn’t until Juanita’s brother, Vance, was born that Linda noticed that Juanita was different. When Linda would walk into a room, little Vance would turn immediately, while Juanita kept her head down.

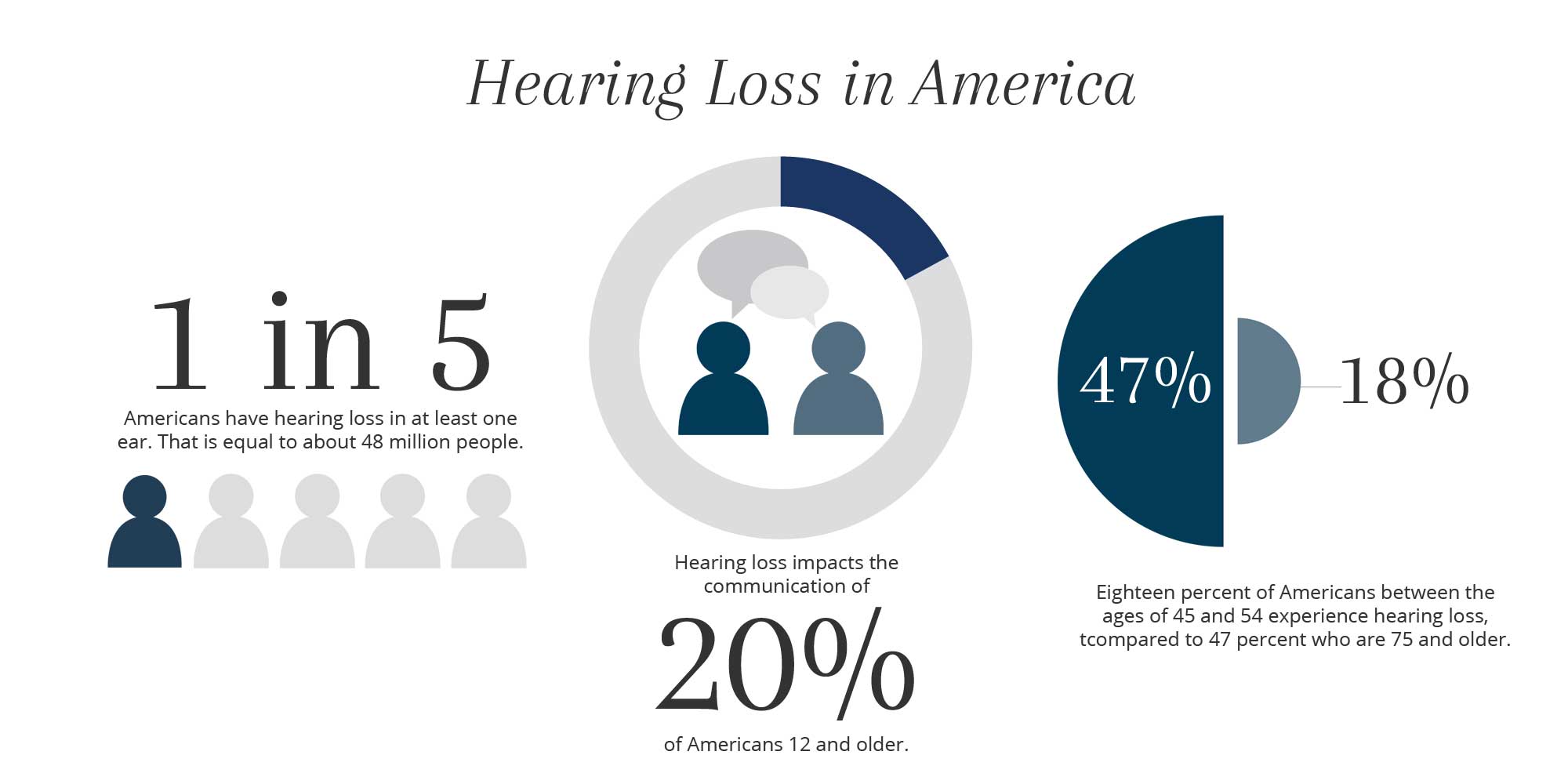

Juanita’s deafness is sensorineural, meaning her auditory nerves are permanently damaged. She has about ten percent of her hearing left, and of that she can only hear lower bass-like tones.

Juanita uses a high-powered, behind-the-ear hearing aid from Germany called the Audifon H70 Super D. Hearing aids are very expensive, ranging in cost anywhere from $3,600 to over $7,000.

Born two months premature and in critical condition, Juanita was kept alive with medicine that also caused irreversible nerve damage in her ears. Though there have been new developments in cochlear implants and other hearing treatments, nothing can fully restore nerve deafness. Juanita uses a high-powered Audifon H70 Super D hearing aid to detect noise around her, but the amplified sound is still distorted. She compares the sound she hears through her hearing aid to taking a tiny photograph and blowing it up until it is pixilated and fuzzy.

Despite the nerve damage, Juanita has trained herself to recognize certain sounds, like her children playing in the room. Although the sound of “mom” is distorted, it is all she knows.

“ There was always music in the house when I was pregnant, and Juanita was listening."

The basement of the Blue Eagle resembles a wine cellar of aging guitars and banjos, their dusty cases lined up like black dominos. Tiny cobwebs hang from the exposed wooden ceiling, swaying in the breeze of three dancing fiddle bows as Juanita, Greg and Liz play the “Skye Boat Song”, a Scottish lullaby. Liz tells Juanita the song's background to give her an understanding of how to play it.

Her fiddle fascination began in a deaf elementary school where teachers had the students feel the vibrations of the violin, but Juanita’s mother thinks her love of music may have began in the womb— when she could hear. “There was always music in the house when I was pregnant,” says Linda, “and Juanita was listening.” Linda remembers her husband coming home from work and blasting Hank Williams and Johnny Cash while she made dinner.

As a little girl, Juanita would place her hand on her father’s guitar while he played to feel the vibrations. “I just like the way my family and other people look when they play music. They seem more relaxed or they seem happier. There was such a change on them and it was like, ‘how could they be that way?’ To see people actually be able to relax and play it’s like, I want that. I think it’s more that than anything else.”

When she was in fifth grade, Juanita transferred from her deaf school to a public school where she was the only deaf student. A new school meant an opportunity to learn her dream instrument, the violin. The small town of Gibsonburg, Ohio didn't have any strings in the school band.

“I was picked on a lot, but they didn’t know better. I’m not mad about it… It was just the way things were. I would just keep going and do the best I can,“ Juanita says.

Trying to prove herself, Juanita entered a piano contest in her elementary music class. “I had never taken lessons and I didn’t know what I was doing. I just started writing notes on paper as a way of visualizing the song. It looked good, going up and down, you know.” She wrote and performed her own piano piece, tying for first place with the best pianist in the class. “[The teachers] didn’t realize I was deaf-deaf. They just thought I had trouble hearing.”

“Everything she wanted to do, we made sure she did,” says Linda who never considered her daughter’s deafness a handicap. The only thing Juanita’s parents discouraged was her stint with the drums, for their own sake.

In the simple florescent light of Blue Eagle, Greg and Juanita’s wedding rings shine against the frets, a sign of their love for each other within their newfound love of music. “With [Greg] playing there, of course, are more vibrations and I can feel it more too. It sort of adds more to the song so I enjoy it more,“ Juanita says.

“Deaf people have their own way of telling stories through sign language,” Juanita says, “It’s a beautiful language,” full of unabated laughter since deaf people aren’t aware of their volume. In Deaf culture big hugs are customary greetings and waving or tapping someone to get their attention is essential.

“My wife is kind of exceptional,” says Greg. “She's kind of an anomaly in the deaf world because she does speak so well.” Thanks to 15 years of intensive speech therapy, few people can tell Juanita is deaf when she speaks. Since the couple’s relationship began, there have been few language barriers when it comes to their love.

The two met when Greg volunteered at a deaf college in Columbus to work as a stenographer for individual deaf students. Juanita was his first student. To further immerse himself in deaf culture, Greg took a sign language class where Juanita happened to be the instructor. “We kept running into each other and decided to quit fighting it and started dating.” After getting married in 2004, they have experienced minor miscommunications, as do any newlyweds.

For example, bedtime pillow talk was trickier than Greg expected. Saying “Goodnight” meant Juanita putting her hearing aid back in, getting her glasses and turning on the light so she could understand what he was trying to tell her.

The tables quickly turn for Greg when he gets together with Juanita’s deaf friends. “I either have to continually interrupt the conversation or I have to sit there completely lost because I don't know what they're saying,” says Greg who understands how isolating social situations can be for his wife.

Beyond language, Juanita must constantly straddle the distinct cultures of the hearing and deaf worlds. The unspoken differences include humor, mannerisms and conversational norms that are unique to each group. While being very literal and blunt may be rude in the hearing world, it is essential for the deaf people who communicate with American Sign Language (ASL). ASL doesn't have as many words as English (roughly 470,000, according to Merriam-Webster), leaving many terms to be communicated through facial expression and body language.

In college, Juanita and her deaf friends would always have to “tone down” their expressive and animated mannerisms when communicating with the hearing. In the company of other deaf people, Juanita picks up her “deaf accent,” talking with big hand gestures that can startle some hearing people.

“I always felt like I had to hold it in,” says Juanita. Even today she tries to monitor the way she talks. “I can see my parents in my mind saying you know, ‘calm down don’t sign, speak.’” Now, a mother of two, she understands that her parents just wanted the best for her.

Back in the lesson, Liz is tells Greg to turn up his volume. Juanita is outplaying him again. “She’s a much better fiddle player than I am,” says Greg. Since she cannot hear the other players, Juanita plays more as a soloist. “She always gets to lead,” says Greg. “Even though I don’t like the attention,” Juanita shyly adds. The cement and stone spackled walls are plastered with hand-scribbled coloring book pages and Thank You notes from tiny-fingered music students, like a quaint music classroom in an elementary school.

Classrooms have been stressful places for Juanita. She struggled in school to keep up with lip-reading what the instructor was saying, getting lost in silent translation, never realizing when the students behind her were asking questions. Most of her learning happened at home as she reread over every textbook and assignment, trying to make up for what she missed during the school day. The late nights of studying paid off and Juanita graduated as valedictorian of her high school.

Being deaf almost got Juanita expelled from Ambassador University in Big Sandy, Texas, which accepted her only after she withheld information about her “disability” on their application. Juanita had to convince skeptical professors to let her keep taking their classes. “They had to learn: Okay, I guess we can accept someone who’s disabled and, it turned out, after me they started accepting other students with disabilities too, which is good.”

Most of Juanita’s life has been about proving herself in the hearing world. “I gotta do well in school, I gotta do well in speaking, I gotta learn to talk, I gotta learn to hear, in other words figure out what’s going on around me…”

But in today’s lesson, Juanita can tune out what is happening around her. The creaking footsteps of Blue Eagle customers and the loud wail of an electric guitar above never distract her from playing the notes on the page.

The real reason why Juanita has learned to play the fiddle is because she craves challenges. “I want to challenge myself to do something that’s genuinely impossible to do,” she says.

Although she has never heard the harmony that fills the room during her fiddle lesson, she has told Liz that sometimes she can hear music in her dreams. Juanita wears a constant faith, like the cross around her neck, that she will hear music someday in heaven.

Everyday holds a new challenge, but Juanita never loses her confidence. “I’ve always believed that I can do anything but hear.”

“ I want to challenge myself to do something that’s genuinely impossible to do."